When I was growing up in a small town on the South Island of New Zealand we went to church on Sunday mornings.

When I was growing up in a small town on the South Island of New Zealand we went to church on Sunday mornings.

My parents were not particularly religious, but I think they wanted my brother and I to have a sense of right and wrong in our lives.

They felt that the best way to instill this in us was to have a preacher inform us in no uncertain terms that if we ever did certain things or didn’t do others, then we were in trouble—BIG trouble.

The morals we were taught in church were basically—do the right thing. But no one ever told me to “think the right thing”.

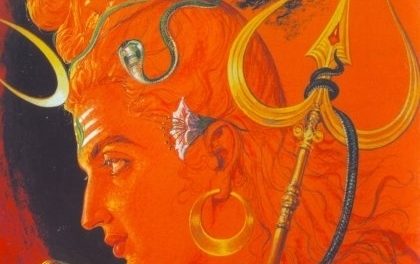

In studying Maharishi Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras recently, I was surprised to find a similar moral code to the ones of my childhood in the form of the yamas and niyamas.

There was a difference here though, in that Maharishi Patanjali presents his morals more like an intelligent choice. Adopt these morals if you want to progress spiritually. They are offered as the means to purify the seeker’s mind.

An interesting distinction arose. All of a sudden I had an on-the-ground reason to adopt these morals; rather than just coming from a distant place of “should.”

In eastern thought, it’s not just our actions that really count but also the intention behind the actions, including both the thinking process and the character of the person. It’s not enough to do good actions to progress on the path; we need to have a good mind as well.

We have to start where we are by moving from the gross to the subtle. Maharishi Patanjali says to start with refining our actions. In transforming how we interact with the people and things around us, we will begin to transform our minds.

So these yamas and niyamas are much more than just a list of ten morals to lead a harmonious life; for a spiritual seeker they are the ten essential ways to transform the mind into a lean, mean, meditating machine.

How do they help us exactly? Anyone who has ever done even a few minutes of meditation or maintaining focus during asana knows what a tough job it is. In fact nothing we will ever do in our whole lives will be harder than being still in one place and holding the mind on one thing.

But why is it so hard? In Maharishi Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras he says:

“Concentration is the confining of the mind within a limited mental area.”

Concentration is simple. In fact it’s so simple we find it terribly difficult. We find this most simple of all tasks to be the most difficult is because we are so complicated!

And so the key to the success in our practice is really to approach it with a simpler attitude and clearer mind. And this is what practicing the yamas and the niyamas does for us.

This kind of makes sense. I don’t get to leave my personality on the shoe rack when I enter the yoga center or meditation room; I practice with this same complicated personality that I do everything else in my life with. By refining my personality, I am really helping by practice.

Below is the list of the yamas and niyamas and my contemplations on how each one can help strengthen my practice: (I invite you to do the same contemplation and see what you come with. It’s a nice exercise.)

Ahimsa (non-violence). If I don’t use any kind of violence to get what I want, I develop an attitude that is calm, patient and compassionate, even in adverse circumstances.

Satyam (truth). If I don’t tell lies about myself or others, I develop an attitude of simplicity and humility: to be purely just myself, no more and no less.

Asteya (non-stealing). If I don’t take anything that isn’t really mine (including praise), I develop an attitude of evenmindedness in all circumstances.

Brahmacharyam (celibacy). If I don’t misuse people or things to try to fill a craving inside myself, I develop an attitude of self-confidence to boldly suggest that my true nature is indeed pure consciousness.

Aparigraha (non-possessiveness). If I don’t accumulate stuff that I don’t use, I develop an attitude of not grasping at or holding onto things, even thoughts.

Saucham (cleanliness). If I keep myself and my environment clean and tidy I develop an attitude of discrimination about which thoughts are helpful to me on the path (and which are not).

Santosham (contentment). If I can be grateful for what I already have in my life, I develop the attitude that true happiness is really already within me.

Tapas (discipline). If I do what I say I’m going to do, I develop an attitude of being able to stay in the present moment.

Svadhyaya (self-study). If I pay close attention to the daily lessons of my life, I develop an attitude of insight into specific ways in which I can become free from sorrow.

Isvara-pranidhanam (surrender to God ). If I can see my own place and purpose in this vast creation, I develop an attitude of fearlessness to become anything and everything I want to be.

This is quite an interesting exercise. By refining these outer aspects of my life, what I am really doing is harmonizing this person I am outside with the one I am on the inside, until finally they become the same person—transparent and pure.

And when we develop this natural harmony and balance, our meditation and yoga practice becomes effortless and blissful.

I remember Amma saying once that there really isn’t an inner world and an outer world; it’s all just one. Perhaps this is what she meant.

May all beings everywhere be happy!

Author: Stuart Macindoe Haran